It was the worst fire in Japan before modern times: the Great Fire of Meireki. Not only did it kill countless people, it also came with a spooky legend.

The third year of the Meireki era was 1657 in the Gregorian calendar. Chinese astrologers have more interesting names for stuff: they gave it the auspiciously unthreatening name Year of the Fire Rooster.

Some shady storytellers who are shabby dressers have used the Great Fire of Meireki to badmouth innocent kimonos. The anti-sartorial propaganda goes something like this:

Once upon a time (in 1657) there was this really pretty kimono that every teenage girl in Edo wanted. It had only one flaw: mysteriously, its owners kept dying. The girl’s family would then sell the kimono to a pawn shop, only for the next fashion-conscious youth to fall for its extreme silky hotness.

One sharp-eyed (and nosy) priest noticed the same garment kept popping up wherever girls died. He had never read any fairy tales or Greek tragedies, so he set out to rectify the problem by burning the kimono.

This backfired.

The flames leapt to the temple, to some nearby houses, and then to the rest of the city. The end.

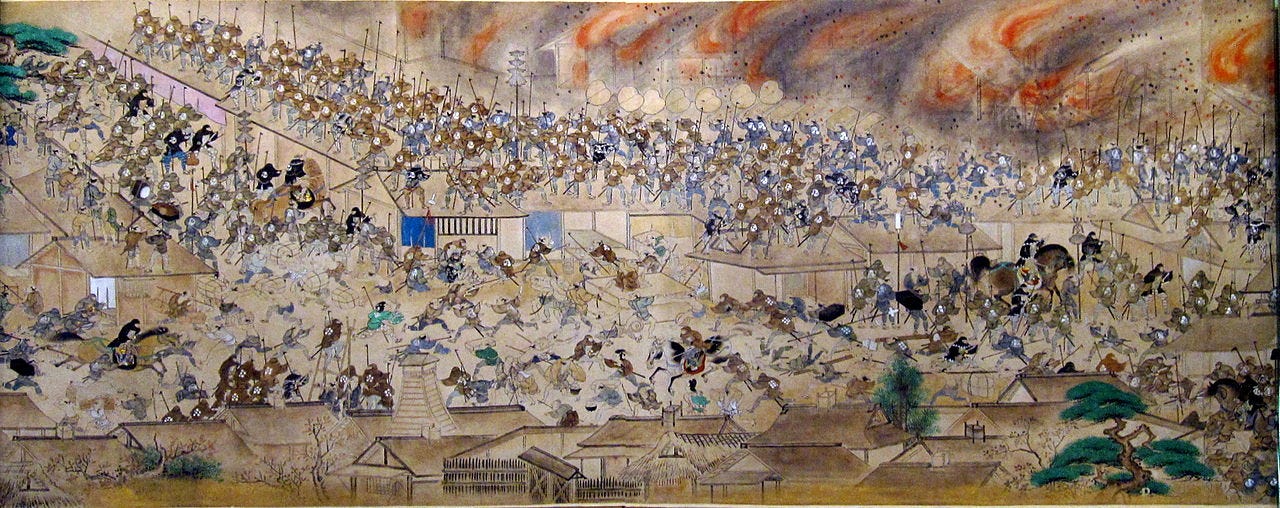

The real story is more sobering. Over the course of three days, three separate fires of unknown origins destroyed between two thirds and three quarters of the capital city of Edo, including the shogun’s castle. After the fires had run their course, a blizzard (which the Chinese astrologers had foolishly failed to warn anyone about) swept in, and many who had escaped the fires died from cold and starvation.

Sources at the time estimated the death toll between 30,000 and 100,000, with the latter figure being generally cited today. Edo’s population before the fire had been around half a million. The city wouldn’t suffer another catastrophe this big until the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 and the firebombing of 1945.

In the aftermath, the government widened Edo’s streets and created public squares to act as firebreaks; they moved many temples, shrines, and residences away from the castle to reduce congestion; they made a permanent, centralized fire brigade to supplement the earlier volunteer and feudal forces; and they imported an early type fire engine from the Netherlands, Japan’s only Western trading partner at the time.

Though these measures helped, Edo continued to be terrorized by fires well into the 1800s.